Writer/Producer/Director Gregory Scott Williams, Jr. has created a solid portrait, packing much of Ms. German’s history, insight and artistic process into a lean twenty minutes. The film is at times, manic, unsettling, melancholy and somehow, ultimately hopeful. It sheds light on the transformative nature of art and the artist’s search for truth and the attempt to make meaning out of incongruous experience. The opening is powerful – visually interesting, gripping and Ms. German is very quickly presented as a big personality with intellect, rhythm and heart. However, I’m not quite sure what to make of the interstitial cards in Ms. German’s voice – the voice appears to be scattered, unfocused, manic, ominously foreboding, brash and blunt with a slightly sad and violent overtone. Nevertheless, the directing, cinematography and editing are concise and focus the mind.

As a subject, Ms. German’s life is in no short supply of dramatic narratives – an extremely talented, black lesbian artist struggling to keep a roof over her head and quite literally to maintain her sanity (she suffers from mental illness including bouts of depression that have brought her to the brink of suicide.) But despite such overwhelming adversity, it is her magnetism as a performer that resonates most throughout the film. Her booming monologues are lyrical and soulful as the blues, painting vivid portraits of the downtrodden and oft forgotten folks.

Her sculptures provide an ironic counterpoint to her performance piece – she constructs ornate black dolls out of papier mache, plaster and a variety of found objects that are beautiful, sad and whimsical all at once. They speak volumes without saying a word. At a single glance, Ms. German’s “tar babies” conjure up hundreds of years of oppression and directly confront and challenge long-standing Eurocentric ideals of beauty. Each sculpture practically cries out for our love, understanding and acceptance despite their stoic countenances.

Ms. German’s work reminded me of a paragraph by Junot Diaz, discussing the influence of Toni Morrison, Octavia Butler and other writers of their generation: “Why these sisters struck me as the most dangerous of artists was because in the work of, say, Morrison, or Octavia Butler, we are shown the awful radiant truth of how profoundly constituted we are of our oppressions. Or said differently: how indissolubly our identities are bound to the regimes that imprison us. These sisters not only describe the grim labyrinth of power that we are in as neocolonial subjects, but they also point out that we play both Theseus and the Minotaur in this nightmare drama. Most importantly these sisters offered strategies of hope, spinning the threads that will make escape from this labyrinth possible. It wasn’t an easy thread to seize—this movement towards liberation required the kind of internal bearing witness of our own role in the social hell of our world that most people would rather not engage in. It was a tough praxis, but a potentially earthshaking one too. Because rather than strike at this issue or that issue, this internal bearing of witness raised the possibility of denying our oppressive regimes the true source of their powers—which is, of course, our consent, our participation. This kind of praxis doesn’t attack the head of the beast, which will only grow back; it strikes directly at the beast’s heart, which we nurture and keep safe in our own.”

There is a profound symmetry in Ms. German’s work as a sculptor and performer – both disciplines manifesting in a sort of soul hollering, beseeching the viewer to recognize America’s shameful legacy of slavery, brutality and injustice, to stare it right in the face, to acknowledge the complicit nature of our relationship as oppressors and oppressed and hopefully to embrace ourselves and one another for the sake of a shared future.

(Review by Mad Matthewz)

“Introducing August Wilson” Blog

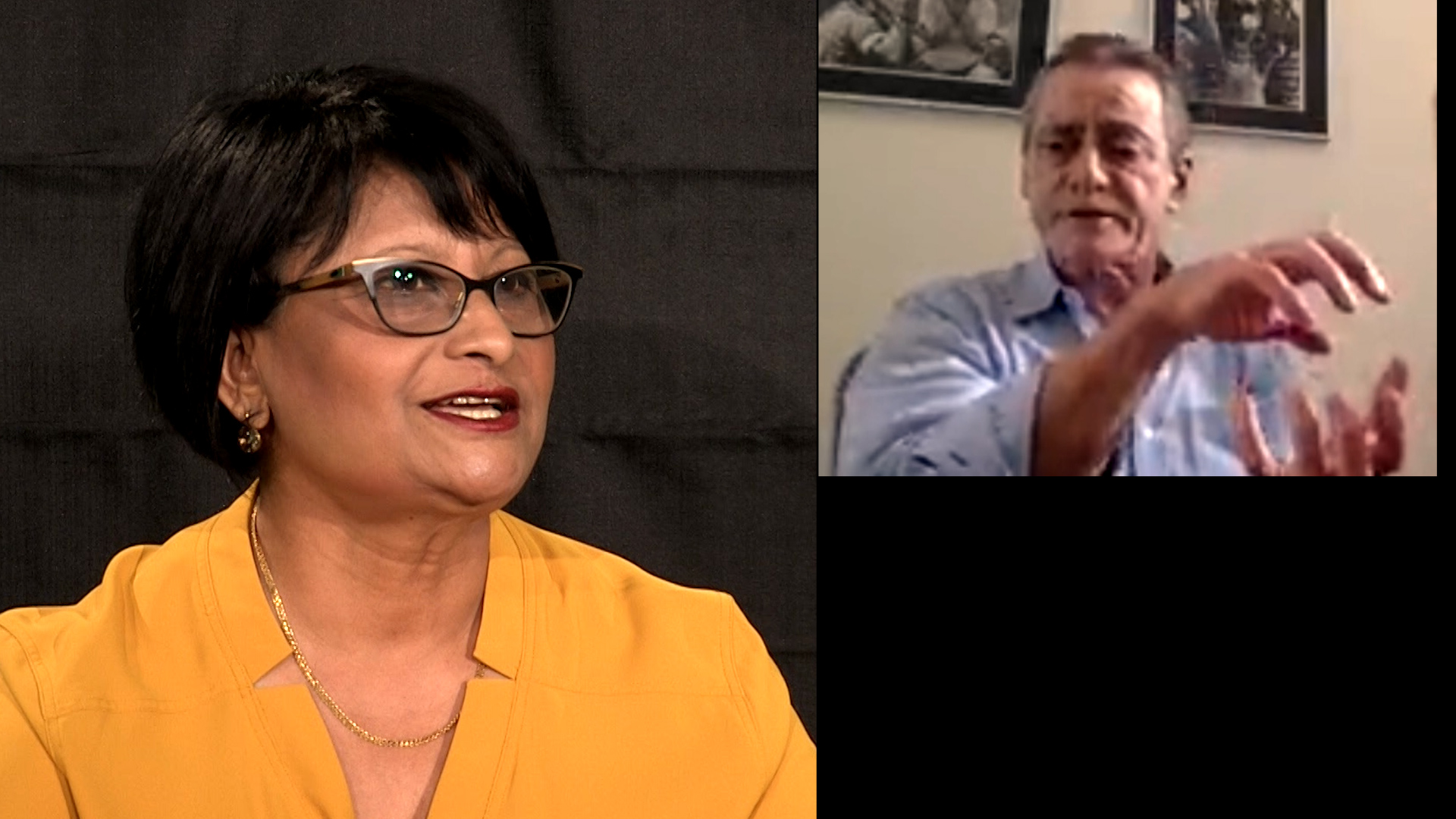

Expectation. Dedication. Responsibility. When I learned that Bill Nunn was willing to participate in the Game Changers Project, I expected to revisit the past: memories of Radio Raheem resurfaced. After seeing School Daze in 1988, there was no question that I was going to Morehouse; and after seeing Do the Right Thing in 1989, my dedication to making films was absolute. So as I planned to meet with Bill, I was certain that Radio Raheem and Bill’s work with Spike Lee would serve as the foundation of the piece we were doing together. I felt a responsibility to share how the work Bill has been involved with has impacted my life.

The first day of shooting changed my perspective. As I observed Bill working with Pittsburgh teenagers during a coaching session at the August Wilson Center, it was clear that the expectations being fulfilled were those Bill held for his students: he expected them to find themselves in the work of August Wilson. Contrary to my initial thoughts, profiling the Bill Nunn Theatre Outreach Program was not an opportunity to pay homage to Bill’s iconic portrayal of Radio Raheem. Instead, the shoot was a refreshing glimpse at the transformative nature of art. I witnessed how “at risk” teenagers embraced ambitious expectations of themselves; discovered the power of dedication to a goal; and accepted the responsibility of knowing and preserving the legacy of August Wilson.

While I was unable to squeeze Radio Raheem into this piece, I certainly hope that I have communicated why Bill Nunn is important to me and why he matters to the kids he continues to influence through his work.

(Gregory Scott Williams, Jr.)